After two hours of snaking through the mountains that form the southwestern boundary of Lake Titicaca, my bus arrived at the Bolivian border. The doorman popped into the back of the bus, “El Estadounidense?” I raised my hand, and he beckoned me to the front of the bus. I sat in the front seat with the doorman and driver until we reached the gate at Peruvian immigration. The bus driver explained that he would chaperone me through the border, helping me to sort out my documents and cut in line to increase the chances I get through without incident.

The Peruvian border agent instructed the bus to disembark, and the driver took me into the Peruvian immigration office. There were only three people waiting in line, but he still told them I had to go in front. I got my stamp and was out of the office before most of the other passengers had gotten off the bus.

After the Peruvian side of the border, one normally has to walk 500m to the immigration office on the Bolivian side of the border. The Peruvian police did a quick inspection of the bus, then gave it a wave and the bus driver drove me to the Bolivian office. The driver rushed me to a small photocopy business just to the side of the immigration office. There is a cottage industry of copy shops on the Bolivian border that provide faked and forged documents to lacking tourists. The driver told them I needed an itinerary. I gave them all my documents which they made copies of for me, then also provided a custom itinerary which weirdly was almost the exact path I was loosely planning to take through Bolivia into Chile. It set me back 30 Bolivianos or ~4 USD.

The bus driver then hurriedly took me by the elbow into the shoebox sized Bolivian immigration office. A line of some 40 people was already stretching out the door. That line was for the normal immigration process. There was another line for foreigners that had to make payments where only three Israeli gentlemen were waiting. The driver physically placed me in line there, and then spoke with a huge 280lbs armed Bolivian commando regulating the normal line. The bus driver instructed me to go to the front of the other line after I paid and to slip the army guy 20 Bolivianos.

The process took almost an hour. I now have a file on me by the Bolivian government and a special page in my passport which says I am imperialist scum, but not yet a known spy or other intelligence community infiltrator, and gives me right of entry for 10 years. All for the low, low price of $160.

I made it back to my bus before a group of South Korean tourists whom apparently had some difficulty, and we shortly departed for Copacabana.

An hour and a half later at 12:30pm, the bus pulled into dusty Copacabana, and parked on the side of a street. I grabbed my backpack from the luggage compartment and headed towards the lake. I stopped in the first hostel I passed by. It was actually more of a hotel than hostel, and I got a private room with shared bathroom for 40 Bolivianos (exchange rate is ~7 BOB/USD). I went out to see the town and find lunch.

Copacabana is a small pueblo on the shore of Lake Titicaca. There’s basically one main street that runs perpendicular to the lake leading to the main dock along which most of the bars, restaurants, and lodging lie. Off the main street, there’s a few residential blocks leading into the hills, and that’s about it. It is a haven for the penniless hippie vagabond types, who hangout along the main street in scores getting high, having digeridoo jam sessions, and selling macramé jewelry and the like (then immediately spending the proceeds on beer)—generally all super good-natured, funny people that are entertaining to shoot the shit with.

The main thing to do in Copacabana is go to Isla del Sol, an island 40 minutes off the coast with indigenous people, Incan ruins, and scenic hiking. Unfortunately, the prior night in Puno I had learned that the people of the island were having a conflict, and the entire northern section, the most scenic and best hiking, was blockaded and tourist entry prohibited. I was planning to stay a night or two on the island, but the blockade put a damper on things.

After a 15B sandwich (no wonder the hippies love this place, so cheap!), I decided to just take an afternoon tour of Isla del Sol. The boat left at 1:30pm and arrived on the island at about 2:15pm. I climbed a flight of stairs leading into the hills of the islands where the locals live. Did I mention that Lake Titicaca is the highest elevation lake in the world? Climbing the stairs, maybe 200m upward, was a task. I was panting like a Siberian sled dog by time I reached the top. I hiked around for about an hour.

It is always amazing seeing how people live in a place like this. They mostly live in wooden, two-room houses with thatched or tin roofs built into the hillsides with a small fenced yard containing an assortment of farm animals. At one point, I passed a lady in traditional garb of what I would guess to be about 75 (although maybe significantly younger—it was hard to tell from her sun-hardened, leathery brown face) with a 60lb load of firework, half her bodyweight, strapped to her back. I was laboring on just my two feet going up the incline, and here’s this old lady, an Incan vestige with corncob pipe, moseying along no problem. And she’s actually smiling! With a big, toothless grin! I said hi and she beamed a greeting I couldn’t understand, and I passed by thinking to myself, “Wow. Just wow.”

I stopped at a few Incan ruins, basically stone houses enduringly built. The Incan knowledge of plate tectonics and adaptation to earthquakes is impressive. They built the houses in an area with frequent earthquakes, and here they are, still standing, hundreds of years later.

As the sun was setting, I boarded my boat for the cruise back to Copacabana. Once the sun goes down it gets really cold, really fast. I was comfortable during the day with just a light sweatshirt, but by time we landed in Copacabana, I could see my breath and my hands and feet felt icy. I hurried home to bundle up, and then wandered out for dinner. I went to a random café on the main strip and was lured into ordering a meat-lovers pizza by enticing pictures in the menu. Damnit, Matt, when are you going to learn?! If they don’t have a brick oven, don’t order pizza in South America! I washed the sorry excuse for pizza down with a 750ml beer (which is the standard size beer in Bolivia—fuck you sissy, imperialist American bootlickers and your wimpy 12oz beers!) and a hot toddy, so I was feeling satisfied by time I left despite my poor ordering habits.

A weird happenstance of my time in this region: in Arequipa, Puno, Copacabana, and La Paz I was regularly waking up after just five or so hours of sleep and feeling completely refreshed, like I didn’t even want to turn over and go back to sleep for another three hours. Interesting, considering the high altitude, thin air, and freezing cold nighttime and morning temperatures of these places. I wonder if there is a scientific explanation for this or it’s just some sort of oddity in my body’s sleep efficacy?

The next morning, I headed out as the sun was rising over the lake, converting the towns tin roofs into gold. I walked about for a bit, my breath forming big grey clouds is the purple morning air. I went to one of the only places that was open at the time, The Eagle and the Condor Café. It’s owned by a guy from Ireland who loves coffee and giving advice to travelers. I was the only person in the place, so naturally we spent the morning talking over several cups of joe and Irish oatmeal.

There was a bus departing for La Paz at 1:30pm. I couldn’t see any reason to stay in Copacabana longer, so bought a ticket.

I spent the next few hours hiking a hill behind Copacabana. This mountain has Incan relics near the top: an Incan gate, the ‘La Horca del Inca’, and some sort of plumbing system carved into the rock. It’s a nice hike, but desolate. There were a couple of spots on rocky precipices with poor footing where you really have to watch your step—if you fall there’s no one around to help. It took me about an hour to climb all the way to the top of the hill, and I was rewarded with wonderful panoramic views stretching all the way back to Puno.

I made it back down the hill by 12:45pm, just enough time to stop at Restaurant Ali for a plato del día. Most plato del días are simple and bland, but Ali treated me to a gourmet lunch: quinoa soup (a specialty of the region), filet of fresh trout with Béarnaise-like sauce, sweet potatoes and sautéed vegetables, and a chocolate ice-cream and mouse pie. Damn, Ali, you outdid yourself! For 50 Bolivianos!

I made it to my bus by 1:40pm, but was right on time. The bus arrived in the city limits of La Paz by 4:30pm, but took what felt like an eternity in horrendous rush hour traffic to travel just a few kilometers and finally arrive at the bus terminal at 6pm.

I took a taxi which took another 40 minutes to go only a couple of kilometers to House Wonderful hostel in the Sopocachi neighborhood.

La Paz is the capital of Bolivia. Home to more than 2.5 million people, it lies in a flat area in the western-central part of the country enclosed on all sides by snowcapped Andean peaks, including the towering, ever-present Illimani mountain. La Paz lies at an altitude of more than 3600m above sea level, making it one of the highest cities on earth. Indeed, I would become winded just walking up streets with an incline. Bolivia isn’t the most developed country in South America, and La Paz is no exception. That said, like any major city, it has it all: many, many barrios sprawling into the hills, referred to as the Altiplano, where the poor live, and more posh neighborhoods such as Sopocachi in the south of the city. The mountains around the city are among the most popular in South America, attracting mountaineers from around the world. One observation, as I began to touch on above: La Paz has, by far, the worst traffic of any place I’ve been in Latin America. Large intersections would commonly look like something from the Middle East: cars and buses facing all different directions inching along in disarray, a mule with pull-cart gumming up the mix, honking cab drivers making hostile gestures out their window, each driver cursing every other driver in the vicinity.

After checking in, I headed out to explore the neighborhood, and found myself in front of a restaurant called Humo. It was a cozy, tasteful place with only about six tables and a small kitchen nearly in the dining room where you could watch the chef prepare the food. It was empty at 8pm on Thursday, which I thought was odd. I was hesitant to take a seat, but the menu looked good. The Argentine head chef/owner came out and greeted me. We got to chatting. He was a younger dude, but had been working in high caliber fine dining restaurants since he was 12. He came to Bolivia just to work in Gustu, one of the top ranked restaurants in South America. He finally decided to open his own place, and Humo was the resulting brainchild.

It turned out to be quite lucky that the restaurant was empty, as the chef turned all his attention to making me an awesome meal. He arranged a special tasting menu for me: an aperitif cocktail, a spicy pumpkin and carrot soup, a smoked salmon dish, braised beef short ribs, a glazed lamb chop, a couple glasses of wine, another couple of dishes I can’t even remember, and a brownie with a smoked homemade coconut ice-cream and a creme brulee-like sauce. All the dishes were impeccably prepared and presented, like something you’d see in a photo of a magazine on an airplane, using all types of fancy culinary techniques like smoke guns. And he explained each dish to me as he served it: why he used certain techniques, how the sweetness of one ingredient balances the acidity and bitterness of the others, etc.

By 9pm, other customers were flooding in, and the Argentine chef seemed almost unhappy they were interrupting the master course he was giving me. In the end, the dude charged me 160 B, ~$23, for a meal that would have probably cost around $150 back home. By the time I left at 10pm, the place was full and people were waiting outside.

The next morning, I went on the free walking tour of La Paz. It made the usual stops, and a couple stops unique to La Paz. One of which was the jail, which operates with its own unique and… uhh… interesting system, made famous by the book Marching Powder. The other place was the Mercado de las Brujas, or the Witches’ Market, where all types of potions and goods for making sacrifices are sold.

After the tour, I went for a teleférico, or gondola, ride up into El Altiplano with Jan from the Czech Republic whom I met on the tour. El Alto was very similar to the hills surrounding Medellin—a place where the poor live and all manner of unsavory, salacious things take place. We wandered around the streets, fending off a couple of roving packs of wild dogs, before finding a lookout to view the city.

In the evening, I went out to dinner with Olivia from the UK, whom I shared a room with at my hostel. We went to Kalakitas, an upscale Mexican restaurant along Calle Sagamaga, the main tourist drag in the historical center of the city. After dinner, I booked a tour to bicycle down Death Road for the next morning.

The next morning, I woke up at 6:30am and made a quick breakfast before heading out into the cold morning and walking to the meeting place for the tour.

At 9am the shuttle bus arrived at 4200m atop a mountain. We suited up into jumpsuits and protective mountain biking gear and were given our bikes. By luck of the draw, I got a rickety hardtail bike, which seemed to be the worst bike out of the entire group. I tested it out and it seemed to function sufficiently.

Our tour group of about 20 people with three guides, set off down a paved mountain road. It was basically a pleasure cruise with no pedaling, just coasting downhill at high speeds. I soon realized my back brakes did not work too well. They slowed me down, but if I really needed to crank down for a quick stop, the brakes squeaked and didn’t lock the rear tire. Nevertheless, I figured the brakes were good enough to get me to the bottom safely. We stopped four times to regroup on the way down 60km of tarmac.

After that, we had a quick snack before setting out on Yungas Road, or Death Road, the (now closed to automobile traffic) former most dangerous road in the world. It’s not a road so much as a narrow, winding, dirt and rock path. This part of the descent was much more challenging than the pleasure cruise, especially with bad brakes. The road hugs the wall of a mountain on the right side and on the left side is an unguarded cliff. It was quite scary to look off the edge at some points. Along the way are countless crosses and shrines to people who died while traversing this road.

It took about two and a half hours to completely descend. At one point in the descent, the path cut to the right around an outcropped part of the wall, then cuts sharply back to the left. I went around the curve to the right at high speed, unable to see the sharp turn back to the left in advance. I cranked on the brakes, but the squeaking, dusty brakes didn’t slow me down enough and my front wheel hit the gutter on the right-hand side of the road sending me over the handlebars into a tumble, landing mostly on my left shoulder and doing a somersault before landing in the ditch with my feet under me in standing position. Perfect 10! I ripped a hole in the shoulder of my thick jumpsuit and had a scrape, but was otherwise fine. But the bike had some problems. I had to do a little repair work on the handlebars and gear shifter to get it back into shape. I had another few close calls, all because, well, I’m a speed demon. The guides kept saying “It’s not a race,” to the group, but, frankly, it’s just way more fun at high speed. In the immortal words of Ricky Bobby, “If you’re not first you’re last!”

Several other people bit the dust as well. A guy from Belgium even went off the road and over the edge—on the left side! I didn’t see it (he was behind me), but others thought they had just witnessed somebody plunge to their death. Fortunately, at the spot the guy went over the edge there was a buffer area of shrubs five feet below the road that caught him before the real drop.

From the windy, cold top at 4200m, we descended all the way down into a hot, tropical, jungle climate, finishing at a lodge at about 1pm where the group had beers and lunch.

I arrived back in La Paz in the evening, and immediately went out to dinner at Café del Mundo for a filling alpaca burger. By time I made it back to my hostel and took a shower, I was all tuckered out and fell fast asleep.

The next morning, I moved into an Airbnb apartment in the lovely Torre Girasol, a luxury building on the main street in Sopocachi. I ran errands and prepared a beef heart stew, then settled in for a day of poker. I was again doing well until the internet sabotaged me by cutting out for 15 minutes a few times around 7pm during the critical junctures of my tournaments. Internet in Bolivia is shit.

Monday, I moved into a new place, Hostel 3600 in Sopocachi.

In the early afternoon, I headed out to inquire about an expedition for the next day to climb Huayna Potosi, a nearby mountain with a summit at over 6000m. Jan had told me about it while riding the teléferico. I had the idea of a serious mountain climb ricocheting around the nether regions of my mind ever since I declined to climb Cotopaxi in Ecuador nearly a year prior. Huayna Potosi is considered one of the least technical mountains over 6000m in the world, perfect for someone who’s never wielded an ice axe or crampons before. After getting the details about the excursion and thinking it over, I booked a three-day tour for the next day.

I spent the day wandering about La Paz, mostly just trying to relax and save energy. I went to the Witches’ Market and bought a potion, Mercado Lanza, Mercado Rodriguez, and lounged in Writer’s Café.

In the evening, I carb loaded with a giant club sandwich at a nice café near my hostel, Ciklik. Then I got to bed good and early.

The next day I packed my daypack with all the warm clothes I had, and put everything else into the storage closet at my hostel.

I met my tour group at 9am. We piled into vans, and were carted two hours to ‘Low Camp’ at 4200m.

We ate lunch together and got to know one another. There was Christian and Jonas (both 28, Norway), Jonnes (23, Netherlands), Ben (30, UK), Luke (29, UK), Hannah (27, UK), a Spanish couple, and a Belgian couple. All first-time mountaineers, except the Belgian couple.

After lunch, we got dressed in our climbing gear (heavy coat and pants, ice climbing boots, crampons, gaiters, climbing harness, balaclava, helmet) and tested our equipment. We set out for an hour hike to a glacier on which we would receive training and practice ice climbing.

At the glacier, I was introduced to my guide, Juan, and paired with Jonnes. Juan is a hard, stony-faced hombre from Northwestern Bolivia. He stands about 5’6”, mostly a wine barrel midsection with short, thick arms and legs. He’s been a mountaineering guide for six years, but generations of experience navigating the Andes hardwired in his DNA. We went over the basics of how to use the ice axe, crampons, and how to move together as tethered unit. While we were practicing scaling the glacier, every time Jonnes or I did something incorrectly, Juan would gravely correct us and end with, “No more mistakes. This is your life, man.”

After a few hours of practice, including climbing straight up a 40-foot ice wall, we hiked down to the lodge at sunset. The practice took place at about 4800m, and although every movement was difficult at that altitude, I didn’t feel light headed or overwhelmed and was cautiously optimistic.

The group had dinner, and then Juan instructed us to get to bed early and rest as much as possible as we wouldn’t be able to get much sleep the next day. I laid in bed at 8pm and was asleep soon after. I tossed and turned most of the night in my sleeping bag, but was super rested by breakfast at 7:30pm.

We packed up, and then hiked 3.5hours to ‘High Camp’ above the snowline at 5200m. Here we had tea, then an early dinner at 5pm, and received instructions for the next day. The climb takes place in early morning darkness because if the sun starts melting the ice that makes the path along the crest to the summit, it becomes very dangerous and people can even get trapped on the mountain. We were to wake up at midnight, have a small meal, then begin the climb by 1am. It would take approximately six hours to reach the summit. We’d have only a short time at the summit, then would have to begin the descent to get back down to the snowpack before sunlight starts melting ice.

The group laid down in our bunks at 6pm. It was still light out. We had six hours to rest, but I doubt I even got one hour of sleep. I was nervous and sleep wouldn’t come. I was actually quite glad when the guides came in and turned on the lights at 12am.

It was a weird, silent breakfast. Even Christian who was normally the class clown, was quiet, pensive.

I suited up and had Juan and another guide check my harness. We assembled behind the lodge and put on our crampons. Juan tied us in: it was Juan in front, me tethered next, and Jonnes in back. I asked Jonnes if he was ready, we bumped ice axes, “Let’s fucken do it!” and we were off.

I made up my mind beforehand I was going to summit. After the day of training and the hike to base camp, I had no illusions this was going to be an easy feat.

The ascent in altitude between low camp and high camp is approximately the same as from high camp to the summit, but the effect on the body is magnitudes greater this morning. Just 20 minutes into the hike and my 20lb ice boots are beginning to feel like aircraft carrier anchors.

At the first break, I check my watch and can’t believe we’ve only been hiking for 45 minutes. It already feels like my body has burned at least every calorie I consumed for breakfast, as I try to choke down a few chocolates between sucking air. I realized I had completely underestimated how demanding it was going to be. Every movement laborious in the altitude, I was already hitting my first ‘wall.’

An hour and a half in, I was light-headed, gasping for air, my heart pounding relentlessly, each step advancing me less than a boot-length.

Three hours into the climb, and I was physically drained. Nothing left. Body staging a mutiny. Positive thinking and mental encouragement having near zero effect. My mind screaming at me to give up.

Fourth hour and I felt like I was on the verge of death. Experiencing some sort of micro-hallucinations: seeing purple and reddish blotches randomly cross my field of vision and thinking I’m hearing someone whispering directly behind me. Mind pleading to quit, I can’t go on, etc. Jonnes is not doing well either. Juan tells us we can do it, and I choose to believe him. I tell myself, “I’m summiting this bitch, or I’m going home in a body bag” (if they can even retrieve my body).

Five hours in, and I can barely move three tiny steps without having to rest. Frozen. Wobbly. Like I could keel over, taking my tethered climbing partner and guide with me, at any moment. But, somehow, I was reaching a place of stillness, transcendence. Ready for death.

The final 300m would normally be terrifying as we advanced upward on a 4-inch wide ice shelf running along the crestline leading to the peak. Free fall on either side of the crest. No thoughts in my head. No longer any fear. Accepting my fate.

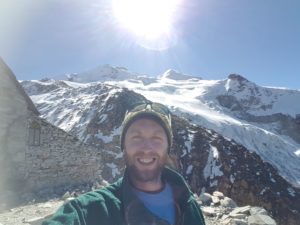

I staggered onto the 4sqft. summit, and turned to help Jonnes up the last few feet. It was surreal. I couldn’t believe I’d actually made it after my mind constantly told me the opposite for the last 4+ hours. I raised my hands in the air and shouted out a triumphant, “Holy Fuck!!!!!” (that admittedly wasn’t that loud because it’s hard to intake enough air, but was enough to get the attention of and encourage the climbers below who waved their ice axes in camaraderie).

After all that, Jonnes and I were the third and fourth climbers of the day to summit. Only one team, the Belgian couple (experienced climbers) made it before us (this is mostly a testament to Juan).

Jonnes and I hugged, patting each other on the back. I asked him to take some photos of me, but to my horror, I pulled my phone from my parka jacket and it was frozen, a sheet of ice covering the screen. Wouldn’t turn on. For the love of God!!! Jonnes tells me that he read online you have to keep the phone close to the body, and digs for his, pulling it out in fully functioning capacity. He was my paparazzi for the summit, but, unfortunately, I wasn’t able to take all the commemorative photos and amazing panoramic shots I’d have like to.

The Belgian couple, Jonnes, and I were lucky to be on the summit during the sunrise.

After about ten minutes at the summit, my beard was beginning to ice up, and we had to descend. For the descent, it was Jonnes first, me second, Juan in back.

Descending the crest was even scarier than climbing it. When going upward you have the luxury of putting your boot in place for the next step, digging the crampons in, and then testing a portion of your weight before committing all your weight to the next step. Descending, there are places where you’re forced to lunge downward with one boot and hope your crampons get a firm hold to support your bodyweight.

At one such juncture, my lunging right crampon broke off a hunk of ice and my foot went falling into the abyss. My ice axe was dug into the crest and I heaved on it with my left hand, wrenching every muscle in my arm and trunk. The axe held, as did my back foot. I ended up in a squat with my butt on the heel of my left boot, my left and right hands clinging onto the handle of the ice axe lodged into the ice crest on the left, and my right foot dangling into the chasm. I had felt my harness pull tight and looked back to see Juan holding the tether strung across his shoulder blades in a wide-legged squat. The ice axe saved me, but it was good to know the tether, which had been an academic exercise heretofore, would’ve provided some sort of additional support.

Three hours later we arrived at High Camp. I don’t know if I’ve ever been so happy to be some place in my whole life. My head feels like it’s the size of a beach ball and has a strange buzzing sensation. Yet somehow the rest of my body has reached some sort of equilibrium—though I know I’m physically exhausted, my body doesn’t feel that horrible anymore and almost like it wants to remain in motion.

I spend a long-time wrestling with my crampons in a post climb stupor. Finally, I get them off and head to my bunk. I consume every gram of nourishment I have in my backpack, and doze off while waiting for the rest of the group to return so we can eat lunch.

After lunch, we then had to suit back up and hike for 1.5 hours back down to the Low Camp. Back at Low Camp, we were picked up 12pm and dropped us off in La Paz at 2pm. On the way back to Hostel 3600, I stopped for a smoothie and sandwich, much needed calories.

At the hostel, I eagerly took a hot shower and then climbed into bed and slept soundly until 7pm. I went out for a big, fat burrito then returned home to go back to bed.

The next morning, I hung around the hostel idly until about noon when I headed down to the main square in Sopocachi. I found an upscale place for coffee and lunch, Wayrura Café. I spent the afternoon walking around the historic center of the city, and visited Writer’s Café again.

In the evening, I stopped in a restaurant whose sign caught my eye, Beef & Beer. After burger and a pint, I was ready to call it a day and headed home to lie in bed and read for a couple hours.

The next morning, I packed up and took a cab to the bus station at 11am. I wasn’t quite sure where to head next, but felt like it was the time to move on. When looking at a map, Cochabamba seemed like a good place to stop and break up the journey between La Paz and Sucre. I found a bus to Cochabamba leaving at 12:30pm. I was still a bit lethargic after the climb, and looked forward to another day of rest during the seven-hour ride to Cochabamba.